|

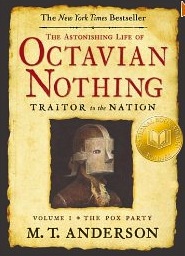

| image from www.amazon.com |

Summary —

Sherman Alexie’s novel, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-time Indian tells the story of a freshman-aged Spokane Indian, Arnold Spirit, Jr. After acting out at school because he realized his geometry text was a generation old, he’s encouraged by his math teacher to find a place that has hope: there is no hope to be found at the reservation. Junior decides to leave the "rez" school to attend an all-white school in a neighboring town, Reardan. He faces objections from the Indians on his reservation, who consider him a race-traitor, and he faces some horrible racism in his new school, since he's the only Indian at that school other than the mascot. But he slowly makes new friends, finds a girlfriend, gets a spot on the varsity basketball team, and in general succeeds in his attempt to find an out from the limited possibilities for a smart kid on the reservation. The narrative is not all joy, as his grandmother is killed by a drunk driver, his father’s best friends is shot to death, and his sister dies in a fire. Despite the support he receives from his immediate family to try a new school, his father is still an alcoholic who occasionally disappears for days at a time when he goes on a bender. On a more positive note, Junior’s new friends all stand up for him when one of the Reardan teachers mocks him for his number of absences. By the end of the novel, Junior even manages to patch things up with Rowdy, his best friend who had been the most angry when Junior decided to go to school at Reardan. The two spend a day playing basketball one-on-one into the evening, best friends once again, as if nothing had ever happened.

Lucien’s thoughts —

I really enjoyed this book. It was equal parts hilarious and heart-wrenching, as Junior often uses humor to staunch the pain. His diary doesn’t flinch from pointing out the inequities of living in poverty, starting the novel with a brief story about how they couldn’t afford to takes his dog to the vet when he got sick, but his dad could afford the bullet needed to put him out of his misery. In general, I think this book is a great example of hope and hard work overcoming adversity. This book would be great for any reader who has ever felt like an outsider because of his or her skin color. The book perfectly captures the ambivalent feelings of leaving your community to strive for something better; it's not all positive emotions. There are real feelings of guilt and betrayal that accompany the feelings of hope. It's a well-written book, full of humor and wit, but also sorrow and pain.

Librarian’s use —

This is a great book to use on a social studies unit on Native Americans and modern life on the reservation. The book points out quite starkly how alcohol is both a coping mechanism and seed of destruction for many Native Americans on the reservation. Arnold uses a lot of humor as his way of dealing with painful subjects, like poverty, racism, depression, and alcoholism, all problems that are plentiful on the reservation. On the other hand, he points out that in some ways, his family is more present to him than the families of some of his white schoolmates, where fathers are too busy to be a part of their kids’ lives. I think the book is a great way to introduce young readers to a voice from a marginalized culture. Alexie plays with cultural stereotypes, fleshing them out to be real people with real problems.

Other reviews —

Sutton, R. (2007). The absolutely true diary of a part-time Indian. Horn book magazine, 83 (5), 563-564.

The line between dramatic monologue, verse novel, and standup comedy gets unequivocally -- and hilariously and triumphantly -- bent in this novel about coming of age on the rez. Urged on by a math teacher whose nose he has just broken, Junior, fourteen, decides to make the iffy commute from his Spokane Indian reservation to attend high school in Reardan, a small town twenty miles away. He's tired of his impoverished circumstances ("Adam and Eve covered their privates with fig leaves; the first Indians covered their privates with their tiny hands"), but while he hopes his new school will offer him a better education, he knows the odds aren't exactly with him: "What was I doing at Reardan, whose mascot was an Indian, thereby making me the only other Indian in town?" But he makes friends (most notably the class dork Gordy), gets a girlfriend, and even (though short, nearsighted, and slightly disabled from birth defects) lands a spot on the varsity basketball team, which inevitably leads to a showdown with his own home team, led by his former best friend Rowdy. Junior's narration is intensely alive and rat-a-tat-tat with short paragraphs and one-liners ("If God hadn't wanted us to masturbate, then God wouldn't have given us thumbs"). The dominant mode of the novel is comic, even though there's plenty of sadness, as when Junior's sister manages to shake off depression long enough to elope -- only to die, passed out from drinking, in a fire. Junior's spirit, though, is unquenchable, and his style inimitable, not least in the take-no-prisoners cartoons he draws (as expertly depicted by comics artist Forney) from his bicultural experience.

Chipman, I. (2007). The absolutely true diary of a part-time Indian. Booklist, 10 (22), 61.

Arnold Spirit, a goofy-looking dork with a decent jumpshot, spends his time lamenting life on the “poor-ass” Spokane Indian reservation, drawing cartoons (which accompany, and often provide more insight than, the narrative), and, along with his aptly named pal Rowdy, laughing those laughs over anything and nothing that affix best friends so intricately together. When a teacher pleads with Arnold to want more, to escape the hopelessness of the rez, Arnold switches to a rich white school and immediately becomes as much an outcast in his own community as he is a curiosity in his new one. He weathers the typical teenage indignations and triumphs like a champ but soon faces far more trying ordeals as his home life begins to crumble and decay amidst the suffocating mire of alcoholism on the reservation. Alexie’s humor and prose are easygoing and well suited to his young audience, and he doesn’t pull many punches as he levels his eye at stereotypes both warranted and inapt. A few of the plotlines fade to gray by the end, but this ultimately affirms the incredible power of best friends to hurt and heal in equal measure. Younger teens looking for the strength to lift themselves out of rough situations would do well to start here.